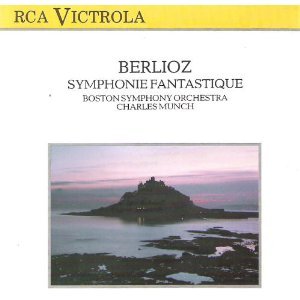

Music Album Review: 'Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique: Boston Symphony Orchestra/Charles Munch'

|

| (C) 1962, 1990 RCA Records/RCA Victrola |

One of my fondest memories from my college days (now almost two decades ago) centers upon the first time I heard Hector Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique: Épisode de la vie d'un artiste ... en cinq parties.

It was a cool (by South Florida standards) afternoon and I was in my Humanities class. Our professor -- Jay Brown, who aside from being an instructor at Miami-Dade Community College was, and still is, a talented musician who can play various instruments, including the glass harmonica -- touched upon many different topics ranging from epistemology to ethics. But on that day we were discussing music: the transition from the Classical period of Mozart to the Romantic era of Beethoven, Schubert, and Berlioz. More to the point, the topic of the afternoon was the advent of the big orchestra, and the prof played a selection or two from Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique: Épisode de la vie d'un artiste ... en cinq parties (Op. 14).

Before he played the first two movements (Reveries, Passions and Un Bal), Prof. Brown explained that Symphonie Fantastique is one of the early examples of program music, i.e. a composition that tells a specific story through musical themes and ideas. It is loosely based on Berlioz's love affair with an English actress but "pumped up" with an almost Stephen King-like turn of events. Supposedly, the musical narrator has taken an overdose of opium, and in his despair, he imagines various events from his courtship with the "beloved."

Berlioz begins the first movement (Reveries and Passions) quietly, in an almost dreamlike mode suggestive of drug-induced sleepiness, as the suicidal "artist" lies in his room and seeing a flood of images from the recent past in his fevered mind. The orchestra then picks up the tempo somewhat like the various memories from his apparently doomed love affair mix with hallucinations. The music shifts from gentle pools of tranquility to dark swirls of strings and brass.

Then, halfway into the first movement, Berlioz introduces the "Beloved" motif which will recur through the entire five-movement work in the same fashion that Richard Wagner would later use in his Ring cycle of operas (and a technique used today in film scores, especially the works of John Williams and James Horner). It is a gentle yet passionate leitmotiv, reflecting the tortured artist's love for the beloved. The movement is, for the most part, warm and hazy, yet ends on a dark and ominous note.

Then, halfway into the first movement, Berlioz introduces the "Beloved" motif which will recur through the entire five-movement work in the same fashion that Richard Wagner would later use in his Ring cycle of operas (and a technique used today in film scores, especially the works of John Williams and James Horner). It is a gentle yet passionate leitmotiv, reflecting the tortured artist's love for the beloved. The movement is, for the most part, warm and hazy, yet ends on a dark and ominous note.

The "Beloved" theme is the "main idea" of Un Bal (A Ball), which Berlioz vividly paints with a waltz-styled orchestration. It is a very Romantic composition, and it evokes images of elegantly dressed Parisian ladies and gentlemen of the early 1820s at a lavish ball. One can almost imagine Berlioz's artist alter ego wandering about until he spies his "beloved," and we can pretty much hear when this happens halfway through the movement when the now-familiar theme joins the dance music. The two musical ideas are interwoven seamlessly, and then the "beloved" theme is reprised by itself before the movement ends on a happy note.

Events turn dramatically in the third movement, "Scene aux Champs" (Scene at the Country), wherein Berlioz musically describes an idyllic outing by the artist and the actress in the countryside. Gentle pastoral music brings to mind scenes of woods, meadows, and dusty paths outside Paris. One can almost see the apparently happy couple having a French styled picnic (complete with wine, cheese, and baguettes) on a grassy meadow near a tree line.

Suddenly, Berlioz telegraphs a turn of events with an almost brutal musical conflict between the "beloved" theme and a darker, sinister theme. The "beloved" theme here sounds almost anguished, for as Prof. Brown told us in that late afternoon, the artist here is imagining that he has murdered the actress. "You can almost see her as she dies," our instructor told us as the music played. And indeed, some 10 minutes into this movement the music reflects the artist's initial sense of disbelief, regret, and unbelievable grief as he realizes -- or imagines -- that he has done a terrible deed.

Suddenly, Berlioz telegraphs a turn of events with an almost brutal musical conflict between the "beloved" theme and a darker, sinister theme. The "beloved" theme here sounds almost anguished, for as Prof. Brown told us in that late afternoon, the artist here is imagining that he has murdered the actress. "You can almost see her as she dies," our instructor told us as the music played. And indeed, some 10 minutes into this movement the music reflects the artist's initial sense of disbelief, regret, and unbelievable grief as he realizes -- or imagines -- that he has done a terrible deed.

Movement four, "Marche Au Supplice" (March to the Scaffold), depicts very vividly the artist's nightmare as it continues. It is dawn, and the jailer has come to the artist's cell, for the sun is up and the guillotine is ready. Berlioz uses brasses, percussion, and strings brilliantly to convey images of the artist being marched to the scaffold as crowds watch in an almost festive atmosphere. Flurries of brass and drums are briefly interrupted by a quiet reprise of the "beloved" motif, then there is a vivid musical description of the execution -- down to a suggestion of a head rolling into the basket, then the movement ends in a celebratory "justice is done" flourish of drums and brass.

Movement five, "Songe d'une Noit du Sabbat" (Dream of a Witches' Sabbath) takes the listener along on the artist's imagined trip to Hell. Here, Berlioz has appropriately dark mood music, including a variation of the beloved's theme that is not the sweet and gentle theme we heard throughout. Instead, it is played as a tortured cackle, and it is joined by a rendition of the Dies Irae (Day of Wrath) Gregorian chant. (Longtime film score fans will recognize this as one of the moodier musical ideas adapted by John Williams in his score for Close Encounters of the Third Kind.) The effect is eerie; one can almost picture the artist cowering in the underworld, as the object of his passions becomes his nemesis in the afterlife.

Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra recorded this classic recording of the Symphonie Fantastique in April of 1962. The album (of the RCA Victrola label) I own is sadly out of print, but Amazon has a more recent (but more expensive) offering on-site.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment